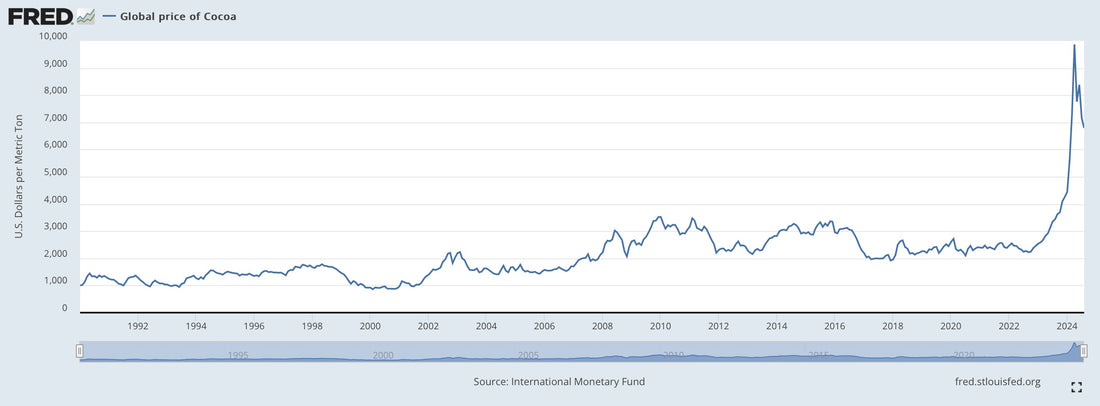

Chocolate season is just around the corner. But first, I want to share a bit of information on something you may have been reading about in recent months—this year’s spike in world cocoa prices. Just look at the chart above. Pretty crazy.

The price on the commodities market appears to have peaked at around $10,000 per metric ton in April and has now dropped somewhat to about $6,800 at the end of August. But that’s still double what it was a year ago.

So what has been going on?

First, it’s worth looking at where cacao is grown. The map below gives an overall view of countries producing cacao, though it doesn’t show some of the nations where smaller amounts are grown.

It’s a pretty narrow range in the tropics, roughly 20 degrees north and south of the equator.

But the share of production is not equal around the globe. Despite cacao being native to the Amazon basin of South America, almost two thirds of cacao bean production is in West Africa, with the vast majority there grown in two nations, Ivory Coast and Ghana (see the blue and black bars below).

This is, in part, where the price spike begins. West African cacao has been beset by two significant climate-influenced issues in recent years. The region has experienced periods of extreme rainfall followed by extreme heat, which have driven outbreaks of fungal “black pod disease” and “swollen shoot virus”. Both these diseases cause significant crop loss if unaddressed—and that is what has been occurring.

The problem is further complicated in West Africa by pressure on cacao farmers from mining interests and low farmer incomes. Despite higher cacao prices, farmer payments in West Africa lag behind, as they are set by government based on prior year prices. This results in farmers being less able to invest in disease prevention and better trees for future years. Ivory Coast and Ghana have recently increased farmers' guaranteed price, but it is still only one third the futures price.

The other factor in the price spike is the commodity market, where cacao traders are betting on future yields, trying to predict what the (largely) West African harvest will bring. A somewhat better yield projection based on weather patterns has caused prices to drop somewhat since a peak in spring.

At the same time, global demand for chocolate continues to grow, and is expected to increase by over 4% annually throughout the decade. As usual, it's all about supply and demand.

Now, how does this affect chocolate?

It’s worth noting there are really two categories of chocolate production: (1) big corporations dominating the chocolate industry, and (2) producers and users of “fine chocolate.”

"Big Chocolate"

Think the chocolate you find in supermarkets. Not just candy bars and supermarket chocolate bars, but also the cocoa in cookies and other baked goods. These are mega-corporations with billions of dollars in revenues owning brands everyone knows. Here’s a chart showing leading chocolate and cocoa manufacturers worldwide as of 2023 in billions of US dollars.

These companies buy large quantities of bulk commodities cacao and produce low-cost chocolate products at mass scale. Different varieties of cacao from different sources, grown for yield rather than distinctive flavor are grouped together for this kind of production.

Fine Chocolate:

In contrast, fine chocolate, is defined “in terms of its flavor, texture and appearance, as well as how its limited ingredients, high cocoa and low sugar content, are sourced and processed.” It represents perhaps 5% of the chocolate market.

Fine chocolate makers and chocolatiers who use fine chocolate source cacao from farmers and plantations placing a premium on trees selected for flavor. Plus, they place a priority on fermentation, drying, and shipping practices that enhance and preserve the high quality cacao beans. This is cacao grown on farms in Ecuador, Peru, Guatemala, Belize, Madagascar, Tanzania, Indonesia and more.

Sometimes fine chocolate makers combine cacao from different origins to produce a certain flavor profile. Other times, they source unique cacao from particular regions or individual plantations and create single-origin chocolate couverture.

As one might expect, fine chocolate makers have generally been paying more for quality cacao for some time, and doing it outside of the commodities market. That said, the increased demand for chocolate, shortages in West Africa, and the overall price increases on the commodities market are driving prices higher for fine chocolate makers and chocolatiers as well.

Moreover, chocolatiers and producers of fine chocolate bars use a significantly higher percentage of cacao in their products than your average supermarket candy bar. Compare a Hershey milk chocolate bar at 11% cacao with fine milk chocolates which often contain 40% to 50% cacao or fine dark chocolates which contain anywhere from 60% to 90% cacao. That’s a major difference in the ingredients cost for fine chocolate users.

Thoughts about pricing:

For Clandestine Chocolates, I buy and use a variety of chocolate couverture from multiple fine chocolate makers, including Felchlin in Switzerland, Valrhona in France, Conexión in Ecuador, and others. These are all companies with a deep commitment to flavor, to working directly with small farmers and cooperatives, and to sustainable practices. I’m often selecting chocolate from particular origins to fit with the theme of a particular collection. For the first collection of the 2024-25 season, I’ll be using at least two chocolates made from heirloom cacao, but more on that later.

Chocolate is the most expensive ingredient in the collections I produce. Well, after labor, that is. In my case, weeks of time go into creating unique designs for my collections that are only used once; drawing them, cutting stencils, spraying transfer sheets.

Many chocolatiers are concerned about how to reconcile the increase in cacao costs, their commitment to quality, and their bottom line. As chocolatiers use up the couverture purchased at lower prices last year, we are faced with the new reality. The chocolate I use for enrobing my fillings has increased in price by more than 50% since last winter.

I'm committed to making chocolates the way I do now, and I'm not going to search out cheaper, less interesting ingredients. I make chocolates because creativity is rewarding, and I want to produce something unique for people to enjoy; something can’t be found anywhere else.

That said, with the increase in cacao and chocolate couverture prices—something unlikely to change—and my commitment to using only the finest of chocolate, I will be increasing the cost of my chocolate collections to $44.00 this year. I appreciate your understanding. And please email me if you have any questions.